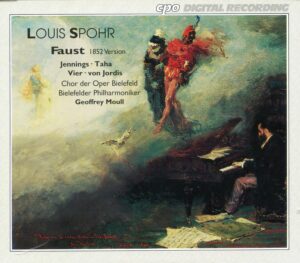

Spohr and Faust. You knew I couldn’t resist writing about that combination, didn’t you? The delay was in finding an adequate recording. Years ago, I got a CD set where the opera was so heavily cut it was incomprehensible. Since then, I’ve gotten a CPO recording of the 1852 version by the Bielefeld Opera. It’s complete or nearly so, but the download from Presto Music doesn’t include a booklet. I need a libretto to follow along, and there’s a libretto for reading or downloading here. It’s got a lot of typos, as if it was made from an uncorrected scan, but it will do. The Capriccio recording has brutal cuts, and I can’t recommend it.

Spohr wrote the first version of Faust in a four-month burst of work in 1813, but it wasn’t performed till 1816. It was a Singspiel, an opera with spoken dialogue rather than recitatives. In 1851 he revised it into a grand opera with recitatives. Oddly, this version was premiered in England in 1852 and sung in Italian.

The opera doesn’t follow Goethe’s version of the Faust legend. It pulls together a few different versions of the story to create a tragedy in which Faust tries to overcome Mephistopheles’ influence but fails. It’s darker than Goethe’s, Gounod’s, and Boito’s treatments. Even in Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust, Marguerite is saved. In Spohr’s opera, the outcome is catastrophic for all the mortal protagonists.

The opera doesn’t follow Goethe’s version of the Faust legend. It pulls together a few different versions of the story to create a tragedy in which Faust tries to overcome Mephistopheles’ influence but fails. It’s darker than Goethe’s, Gounod’s, and Boito’s treatments. Even in Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust, Marguerite is saved. In Spohr’s opera, the outcome is catastrophic for all the mortal protagonists.

This Faust is morally weak. Three times he renounces his pact with Mephistopheles, who agrees the first two times to release him, but he changes his mind when he realizes how much danger he faces. The third time, Mephisto tells him it’s too late. He insists at the end that his intentions were good, excusing his repeated deceptions, coercion of Kunigunde’s love with a potion, and at least one murder. There are points where he may hold the audience’s sympathy, especially when he leads the rescue of the kidnapped Kunigunde (before deciding he wants her for himself), but they don’t last. He isn’t even a larger-than-life villain like Don Giovanni.

Some of my favorite musical moments:

- The overture, which is by far the most-performed part of the opera. It presents the spirit of relentless striving which is associated with Faust. Some of its motifs recur in the opera.

- The duet for Faust and Röschen, “Folg dem Freunde mit Vertrauen.” It’s followed by Mephistopheles rushing in and singing, “Schnell rettet euch!” (Quick, save yourselves!) Wagner must have known about this when he wrote Tristan und Isolde.

- Kunigunde’s first-act aria, “Ja, ich fühl es, treue Liebe.” The “true love” she feels is for her fiancé Hugo. In the second part of this slow-fast aria, she defies Gulf, who has taken her captive. Clive Brown notes the use of the “Hell” motif as she sings that cunning and malice must fail before love.

- Mephistopheles’ summoning the witch Sycorax near the beginning of Act II. Nice and creepy. If the name sounds familiar, it’s because it’s also the name of Caliban’s mother in Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

- Röschen’s cavatina, “Dürft’ich mich nennen sein eigen.” Spohr sticks close to his Mozartean side here, producing a piece of great beauty.

- The final scene, in which Faust meets his well-deserved fate.

Some parts don’t work as well. At the end of the second act, Faust kills Hugo at the latter’s wedding with Kunigunde. Spohr is too constrained by the conventions of a second-act finale to properly convey the chorus’s horror at the murder.

However, the third act makes up for it. The text is a powerful piece of dramatic writing, and Spohr gives it music to match. It seems that Faust may yet escape Mephistopheles’ grip if he can go back to Röschen. However, Röschen encounters Kunigunde and blames her for having stolen Faust from her. Kunigunde, for her part, wants revenge on Faust for betraying her. When she approaches him, he calls on Mephisto for help, sealing his fate. An innocent man has been accused of Hugo’s murder, but witnesses disclose that Faust is the real killer — and if you thought Kunigunde was mad at him before! Röschen, seeing what Faust is really like, commits suicide. His friends turn away from him. He’s left all alone, and demons carry him off to Hell in a conclusion reminiscent of Don Giovanni. The orchestra fades out on the empty stage, then marks the end with two measures of fortissimo C minor chords.

Spohr’s Faust is never going to displace Gounod’s from the stage, but it’s worth hearing.

This article is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC license. That says you can use it however you want — for instance, in program notes — provided you give me credit by name and aren’t making money off it. (If you are making money, that’s fine, but I expect a cut. Talk to me.)