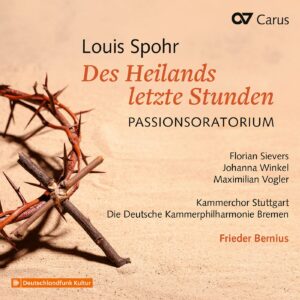

A new release of Spohr’s oratorio, Des Heilands letzte Stunden (the Savior’s last hours), is out from Carus-Verlag. The solo singers are Florian Sievers, Johanna Winkel, Maximilian Vogler, Arttu Kataja, Thomas E. Bauer, Felix Rathgeber, and Magnus Piontek. The chorus is the Kammerchor Stuttgart, and the orchestra the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen. It covers the same ground as Bach’s Passions, from Judas’s betrayal of Jesus to his crucifixion. A booklet in English and German contains Johann Friedrich Rochlitz’ full text with a loose translation, as well as detailed notes.

This oratorio came after Die letzten Dinge, also with text by Rochlitz. It premiered in Kassel in 1835. The earlier oratorio is a disaster movie in music. This is a more introspective work. Unlike Bach’s Passions, this “passion oratorio” tells the story primarily from the perspective of Jesus’s followers. The numbers are mostly dedicated to showing their reactions to his capture, trial, and crucifixion. Bach tells the story from a cosmic perspective; Spohr’s oratorio gets very close to the people portrayed. Even Judas is somewhat sympathetic as he expresses his terror over the situation he’s gotten himself into.

Caiphas and the council of priests are the clear villains. Pilate is completely written out of the story. The most menacing lines of recitative go to Philo, a priest invented for this oratorio. Jesus has only a small vocal part; the representation of Jesus by a solo voice was controversial at the time. A London performance in 1852 had Jesus’s lines sung by John.

Caiphas and the council of priests are the clear villains. Pilate is completely written out of the story. The most menacing lines of recitative go to Philo, a priest invented for this oratorio. Jesus has only a small vocal part; the representation of Jesus by a solo voice was controversial at the time. A London performance in 1852 had Jesus’s lines sung by John.

Mary, Jesus’s mother, has a large part, probably so soprano numbers could be included. Her aria “Rufe aus der Welt voll Mängel” is a gem, accompanied by a chamber ensemble featuring a harp. Spohr’s wife Dorette, a master harpist, had died half a year before the premiere; I don’t know if he originally intended her to perform in it. Most of the numbers are short, and the longer ones have a significant amount of text; it’s a different approach from Bach, who often built long solos around a few words.

John, who functions as the narrator, describes Jesus’s death moment by moment in a very effective recitative. This is followed by the first time in the oratorio Spohr really lets the fireworks go off, as the land turns dark and dead people rise from their graves. (It’s in the Bible!) The piece uses no less than six tympani. It reminds me of “Gefallen ist Babylon” in Die letzten Dinge.

There’s a disturbing aspect to this chorus, though. The chorus — apparently representing the Jewish people — proclaims strenuously that they are innocent and only Caiphas is to blame. The Almighty doesn’t hear them, and they flee to the Temple. Joseph of Arimathea responds: “Flee the avenger in the clouds. You can’t flee the avenger in your heart.” This is the old “Christ-killer” trope, which was still common in nineteenth-century Germany.

Des Heilands letzte Stunden isn’t likely to become one of my favorite Spohr works. As a non-Christian, I don’t get much out of a fictionalized version of the trial and execution of an innocent man two thousand years ago. Still, I’m glad to see a new recording of a Spohr oratorio. His third oratorio, Der Fall Babylons (The Fall of Babylon) has also had a recent release, from Coviello.